Date first published: 02/02/2023

Key sectors: all; defence

Key risks: civil unrest; war on land

Risk development

On 16 May 2022 the previous Swedish government, led by the centre-left Magdalena Andersson, decided to apply for NATO membership. The decision was taken after the Foreign Ministry drafted a report on the consequences of Russia’s war in Ukraine on the country’s national security, concluding that membership in NATO has a conflict-deterring effect. Sweden and Finland applied to join the alliance together.

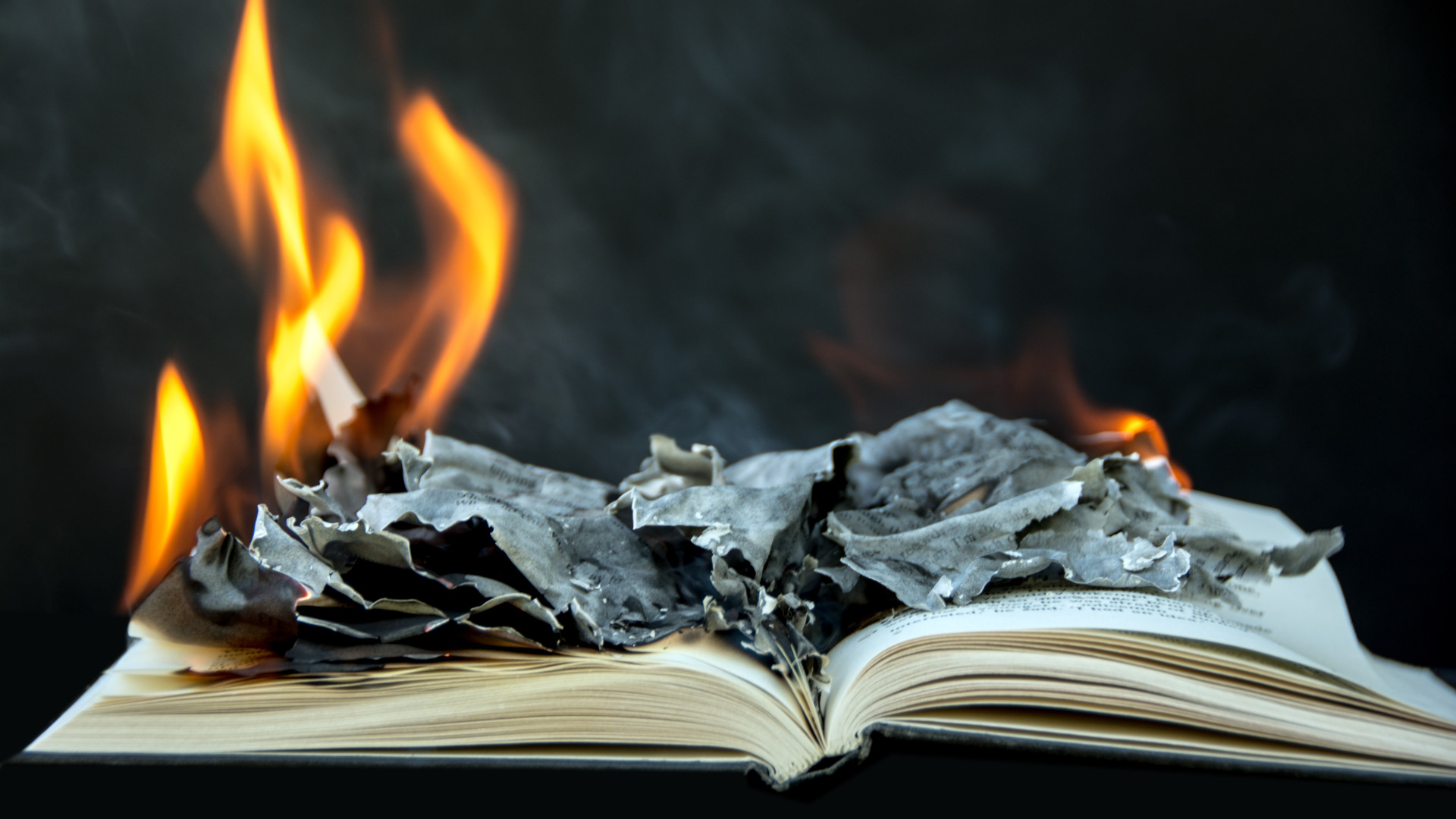

Ankara appeared to be the primary stumbling block for both countries’ NATO bids, initially citing concerns over Sweden harbouring members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a political organisation and armed militant group in Turkey, the US and the EU listed as a “terrorist group”. These concerns appeared to ease in June 2022 after Helsinki and Stockholm signed a deal with Ankara pledging to end support for the Kurdish militants. However, Ankara continued to voice frustrations with the slow progress of the talks and became increasingly hostile towards Sweden’s application after a puppet of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was hung from its feet on 12 January and Rasmus Paludan, a far-right politician, burned a copy of the Quran outside the Turkish embassy in Stockholm on 21 January. In response to these incidents, Erdogan declared on 23 January that Stockholm could no longer expect Turkey’s support for its NATO bid.

Why it matters

Stockholm’s Foreign Ministry stated in the national security report that Russian provocations and countermeasures could not be ruled out during a transition period ahead of Sweden’s NATO accession. These concerns were confirmed when it was revealed that Paludan’s demonstration permit was paid for by Chang Frick, a far-right journalist with links to the Kremlin.

Moscow’s alleged implication in the Quran-burning protest, is part of its efforts to sow discord among NATO allies and weaken Sweden and Finland’s joint accession process. Following Paludan’s demonstration, Finland’s Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto implied that Helsinki might have to pursue NATO accession without Sweden. Although Haavisto later expressed the wish to continue the bid with Sweden, Stockholm is increasingly concerned that it will have to pursue the process of joining NATO on its own.

Background

Although Sweden and NATO have held joint military exercises since 2013, Stockholm’s application put an end to its 200-year-long tradition of neutrality. Increasingly tense relations with Ankara have now left the country in a limbo – neither neutral, nor formally part of a military alliance.

Erdogan used the incidents in Sweden for political gains ahead of upcoming general elections on 18 June as most polls anticipate a tight race. His nationalist and increasingly assertive foreign policy has boosted his popularity as he attempts to distract voters from the ongoing economic crisis.

Risk outlook

It appears increasingly unlikely that Ankara will ratify Sweden’s NATO bid before the elections, although Washington holds a significant leverage over Ankara by withholding the delivery of purchased F-16 fighter jets to the Turkish military. Whether the Biden administration choose to use that leverage to support Sweden’s bid remains to be seen. Sweden’s national security will remain compromised pending NATO accession but overt military aggression from Russia towards the country is highly unlikely. However, hybrid attacks and provocations cannot be ruled out, including further Moscow-backed ultra-right protests.

Although Helsinki has implied it may have to pursue NATO membership on its own, it is likely that Sweden and Finland’s brotherly relations will motivate Helsinki to pause its accession process until after the Turkish elections. Sweden will wait patiently but is unlikely to make significant concessions in areas including free speech, human rights and asylum laws.