Date first published: 6/11/2018

Key sectors: all

Key risks: political instability; debt; investor confidence

On 26 October, President Maithripala Sirisena dismissed Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and replaced him with ex-president Mahinda Rajapaksa, a former authoritarian strongman accused of nepotism, corruption and human rights violations. The move, which Wickremesinghe argues was unconstitutional, set into motion a series of events that reveals a deep political divide in Colombo. The constitutional crisis is set to continue at least until a parliamentary vote of confidence is held, but parliament was suspended and is not set to reconvene until 14 November. The outcome of the crisis is likely to have a lasting impact not only on Sri Lanka’s domestic politics, but also on its economy and foreign policy.

Tensions between Sirisena and Wickremesinghe have long threatened to boil over. Sirisena blames Wickremesinghe for the country’s slow economic growth and has objected to investigations into crimes committed by the military during the civil war that ended with the defeat of the Tamil Tigers in May 2009 under Rajapaksa’s rule. The President’s public reasoning behind the dismissal however, was the alleged involvement of a cabinet minister in an assassination attempt against him.

Wickremesinghe survived a no-confidence vote in April, would likely have been able to prove majority support in parliament immediately after his dismissal. However, Sirisena suspended parliament on 27 October in an apparent attempt to prevent that outcome. Although Wickremesinghe’s United National Party (UNP) submitted a no-confidence motion against Rajapaksa on 2 November – the motion reportedly has the backing of 118 parliamentarians, exceeding the 113-majority required – Wickremesinghe’s support base is weakening. Rajapaksa is already summoning senior military leaders to garner their support, with some previously uncommitted MPs believed to be crossing to his side.

Rajapaksa’s return to power would affect investor confidence. Concerns over the political crisis and Rajapaka’s human rights record has already led the US to put on hold a US$500m aid programme, while Japan has frozen a US$1.4bln soft loan for a light railway project in Colombo. The ensuing political uncertainty could damage Colombo’s ability to refinance external debt in 2019.

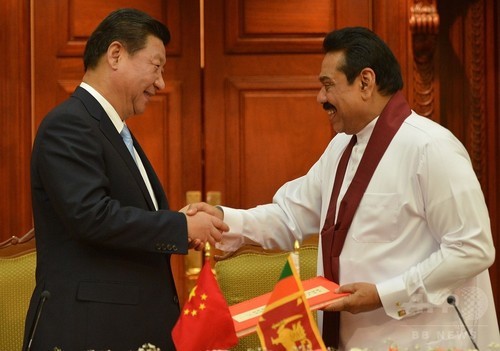

Rajapaksa’s ties with Beijing would reverse Wickremesinghe’s balancing between China and India. Rajapaksa would likely push for more new Chinese investments and this does not bode well for foreign debt, which ballooned during Rajapaksa’s tenure as president. The infamous failure of the Hambantota port project was a wakeup call for many developing countries reliant on Chinese lending. The debt restructure deal that involved the handover of the port’s majority ownership for 99 years provoked accusations that China’s Belt and Road Initiative was a means to entrap developing countries in debt.

It remains unclear how the political crisis will unfold. While Sirisena has indicated a floor vote would not be held when parliament is reconvened, domestic and international pressure will likely compel a parliamentary vote to decide the constitutional prime minister. It is unclear how Wickremesinghe’s supporters would accept defeat in a confidence vote. Despite major protests around Colombo and warnings of ‘bloodshed’, political violence has been relatively limited. On 28 October, one person was killed, and two others injured when the Petroleum Minister’s bodyguard fired at protesters showing their support for Sirisena. Yet, whether it is Wickremesinghe or Rajapaksa that eventually consolidates power, political uncertainty is inescapable.