Date first published: 15 October 2019

Key sectors: all

Key risks: political violence; internal conflict

On 13 October, during the latest wave of city-wide anti-government unrest, an improvised explosive device (IED) hidden in a bush was detonated via mobile phone on Nathan road in Mong Kok, one of the many hotspots of the violent upheaval seen in Hong Kong in recent weeks. The explosion caused no damage or injuries, narrowly missing a passing police vehicle. Whether or not it is confirmed that the IED was planted by anti-government protesters, the incident reflects an escalation in the tactics of hardline protesters since late September.

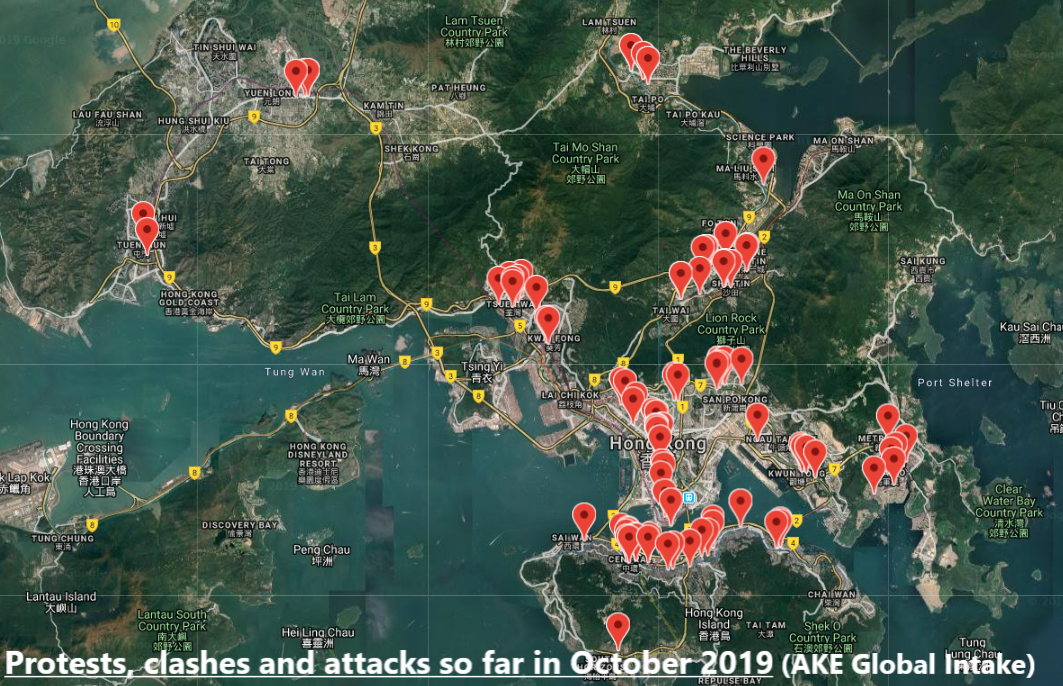

Protests in Hong Kong began nearly 20 weeks ago over a contentious bill that would have allowed extraditions of Hong Kong residents to mainland China. Beleaguered Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced the extradition bill’s withdrawal on 4 September. Nevertheless, protests have continued and have adopted a now recurrent pattern of targeted attacks on entities and businesses with ties to mainland China, or that oppose the protests. The security situation began to deteriorate further in the days leading up to Chinese National Day on 1 October, which was celebrated grandly in Beijing. Meanwhile, protests and clashes flared in Hong Kong, with hundreds of thousands marching across the city centre. Protesters threw firebombs at police lines and police stations and vandalised pro-China buildings and assets. 25 of 91 MTR stations were forced to close. Police fired live fire rounds in two locations, with one protester severely injured after he was shot in the chest.

On 4 October – in an unprecedented enactment of colonial-era emergency powers – Lam further aggravated the situation by announcing an anti-mask law, which took effect at midnight on that day. The announcement sparked lunchtime rallies by thousands of office workers which deteriorated into violent unrest later in the day. The entire MTR network was suspended as protesters vandalised several stations and clashed with police across the territory, including in previously unaffected areas like Aberdeen. As seen in previous days, assets with pro-China ties were targeted and set on fire in destructive rampages, including Bank of China and China Construction Bank branches, as well as China Mobile shops. Violent unrest and vandalism continued for another three consecutive days before protests broke out again over the weekend on 12-13 October. Recent violence includes direct attacks on the Hong Kong Police Force by radical protesters armed with petrol bombs, bricks and both blunt and sharp objects. Aside from the IED explosion, which authorities called a targeted attack on police, an officer was also slashed in the neck with a boxcutter on 13 October.

Unlike the now widely used firebombs, IEDs require a higher degree of skill to manufacture. It remains unclear how lethal the device that went off on 13 October was, and therefore how much of an escalation it represents. Similarly, with no anti-government voice having claimed the attack, some have accused the police of planting the IED themselves to justify tougher measures against protesters. In any case, the incident is indicative of a new phase in the protests, wherein security forces are struggling to contain direct attacks on police and assets linked to mainland China. Hardliners, many of which are teenagers, will likely persist on their track to establish themselves as the linchpins of the anti-government movement, while the moderates will increasingly look to distance themselves from the violence.