Date first published: 28/09/2020

Key sectors: oil & gas; infrastructure

Key risks: energy security; sanctions

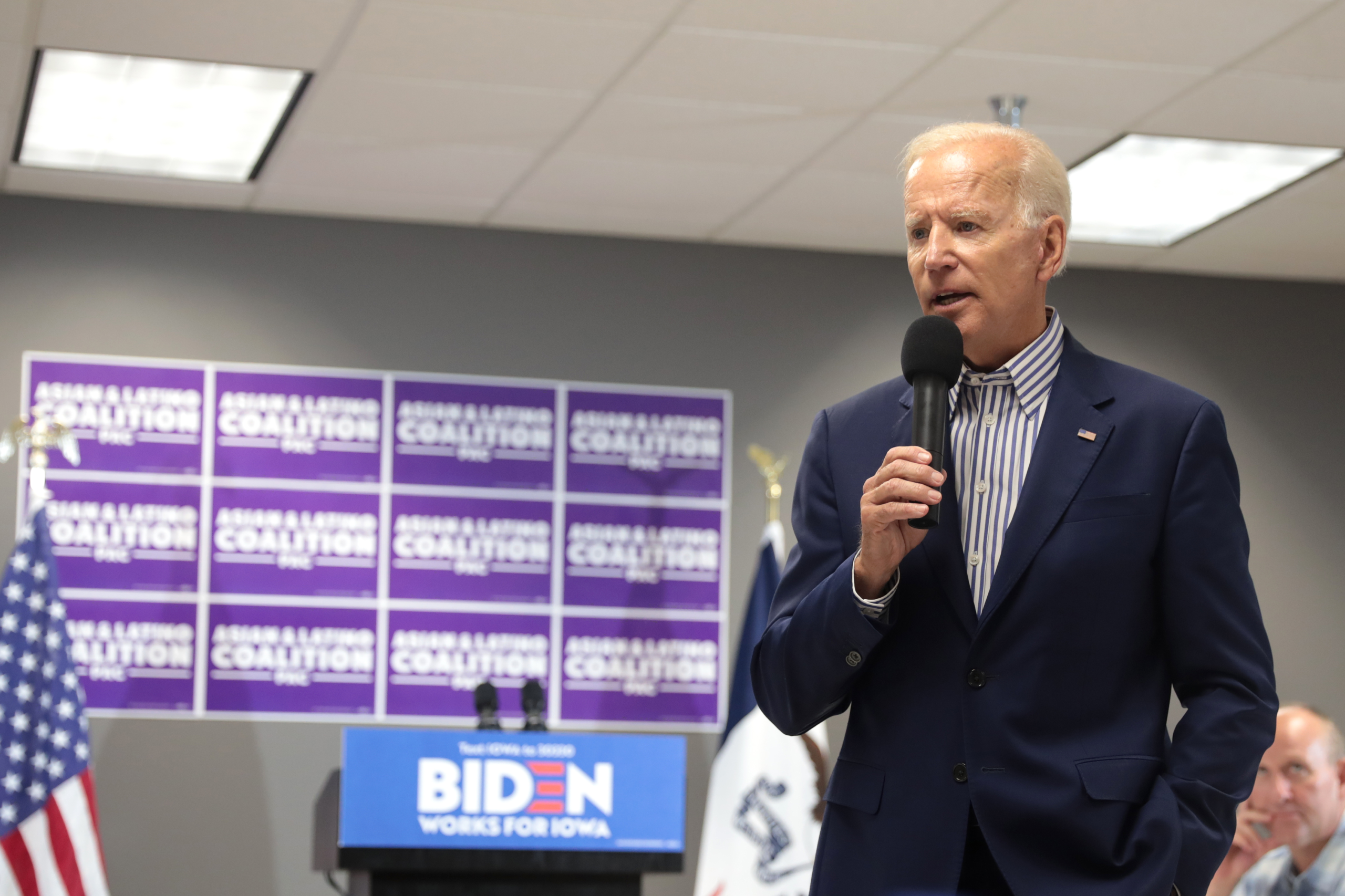

US Presidential Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s campaign strategy has intentionally been devoid of bombastic policy declarations. His chances of winning the 3 November election are seen as largely resting on making the presidential vote a referendum on incumbent President Donald Trump. The fight which erupted surrounding the new opening of a seat on the Supreme Court following Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death has interrupted this, and will bring reproductive rights and healthcare issues back to the fore. Yet neither Trump nor Biden’s foreign policy agenda has been a major issue in the campaign, and this is likely to stay this way as the presidential race enters its final phase. The fact Biden and many of his key advisors have an established foreign policy track record dating back to their time in the Obama Administration means that there are relatively few ‘unknowns’ as to how a Biden Administration would view the world.

A hypothetical Biden administration’s approach to Russia is likely to remain broadly in line with that of the late Obama Administration, as would its support for European institutions and relative coolness to Brexit Britain. It would likely differ from the Trump administration by reversing its aid and development support in more frontier and emerging markets in Latin America and Africa in particular. Biden has signalled he would likely take a harder line on Beijing than the Obama Administration did, backed by increasingly bipartisan support for such an agenda. One major unknown, however, remains – how a Biden Administration would handle relations with Saudi Arabia.

Riyadh has long been one of the US’ closest allies. Its leadership in the Gulf Cooperation Council has helped Washington build similarly close ties with other Gulf neighbours, and its historic role as the world’s largest oil exporter – a position developed in part thanks to sustained US investment – has enabled a mutually beneficial partnership on a host of issues. Since Obama left office in January 2017, however, Riyadh has undergone a series of dramatic structural and personnel changes that have recast its position in the global sphere. It is no longer guaranteed that Riyadh will remain in Washington’s good graces.

In fact, during a November 2019 Democratic debate, Biden warned his administration would “make them…the pariah that they are”.

Two key factors are at play here: Firstly, the global oil gut that shows no signs of abating particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage, reducing the efficacy of Riyadh’s oil as a key point of leverage. Secondly the rise of Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman, also known as MbS, the changes in Saudi governance and society that he has implemented and his unique approach to human rights and Saudi foreign policy.

The growth of the US shale oil industry and the weakening of Riyadh’s position would not be new factors to a Biden Administration. Global oil prices collapsed already in 2014/2015 – the first time that Riyadh targeted US shale producers – before recovering in the run up to the December 2016 deal which brought Saudi Arabia and Russia together in OPEC+. Although that alliance foundered again at the start of this year it was rapidly put back together. Nevertheless, it has become clear that Washington will no longer be as dependent on Riyadh’s oil. Furthermore, China has become established as Riyadh’s main buyer, while the Saudi-Russian economic alignment is an underappreciated new geopolitical dynamic, and one that will not be appreciated by policymakers in Washington, particularly under a Biden administration. The key uniting factor in OPEC+ has not been the universal interest of its members to raise oil prices – this has always been in their mutual interest – but rather that they are now competing for market share with US shale, not just one another.

In fact, that US-Saudi relations have not already come to a head in the last four years is largely due to the second factor, the rise of MbS. The Crown Prince’s ascent to power began while Biden was still serving as vice president, having been appointed deputy crown prince and defence minister just three months after the ascension to the throne of his father, King Salman, in 2015. From the onset he took a leading role in policy, guiding Saudi Arabia into the conflict in Yemen, supported by both the neighbouring United Arab Emirates and the United States. Such direct military intervention abroad marked a new leaf for Saudi foreign policy, but would ultimately serve as a harbinger of far greater changes to come.

Since MbS was named Crown Prince in 2017, he has significantly recast Riyadh’s role in the region. His ‘Vision 2030’ has pushed for the relaxation of religious restrictions on women’s rights and opened Saudi Arabia ever so slightly to Western cultural influences. However, he has also courted controversy. The 2018 murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi – himself a liberal who critiqued MbS’ efforts as mere window dressing to sugar coat his usurpation of power – prompted international opprobrium, to put it mildly.

MbS has also openly associated himself with Trump and his son-in-law Jared Kushner. Their interests were primarily aligned by mutual opposition to the Obama Administration’s Iran nuclear agreement, commonly known as the JCPOA, but since they have moved from strength to strength, making the relationship arguably the closest yet between historical administrations. Saudi Arabia prominently hosted one of Trump’s first major foreign visits of his presidency, and he has been keen to establish himself as one of Trump’s major foreign partners. For example, Riyadh would have to have at least tacitly approved of the Israel-UAE normalisation agreement, as well as that between Tel Aviv and Bahrain finalised shortly thereafter. Trump now claims these deals as a successful example of his administration’s foreign policy going into the election

At the same time, however, MbS’s actions has chafed much of the broader US foreign policy establishment. To a certain extent, allying himself so closely with Trump was always likely to do so, given the hyper partisan US political environment and the fact that many stalwarts of Republican foreign policy circles were among the most prominent ‘Never Trumpers.’ Khashoggi’s assassination was seen as crossing a line no ostensible US ally had been willing to cross in the post-Cold War era given that Khashoggi was a columnist for a major US media outlet, the Washington Post. Furthermore, the young prince’s actions since his ascension to crown prince appear to have been highly erratic.

This is evident both with regards to the prince’s domestic and foreign policy actions. Much attention was paid in 2017 to MbS’s purges of the broader Saudi elite, many of whom are long-time US partners. Among those detained in MbS’ infamous 2017 roundup of Saudi businessmen and officials was billionaire Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, who long has been a prominent investor in the West. Furthermore, MbS has placed former defence minister and crown prince Muhammad bin Nayaf (MbN), long seen as the West’s leading partner in the Kingdom in counterterrorism issues, under house arrest essentially since King Salman replaced him with MbS as crown prince in June 2017. Round ups of dozens of other Saudi princes who could be perceived to have residual loyalty to MbN also took place in March under the auspices of the prince’s ‘crackdown on corruption’.

Latterly, underscoring the erraticism of his foreign policy, in 2018 the prince was responsible for Saudi Arabia suspending diplomatic ties with Canada after Canada’s foreign ministry tweeted a demand to release jailed Saudi human rights activists. Although economic damage from the row was low overall, Riyadh froze new trade and investment business. Expelled Canada’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, recalled the Saudi envoy and divested of Canadian cash, bond and equity holdings from its central bank and pension funds. Most importantly it complicated a significant arms deal with General Dynamic for CAD15bln, negotiations for which are ongoing over two years later.

Despite the backlash against Khashoggi’s murder, which appeared to temporarily pause MbS’ international efforts, there is concern that his erratic actions are escalating. Most recently, Lebanese-American former FBI agent Ali Soufan – who rose to prominence for his anti-terrorism work and research on al-Qaeda – accused MbS of orchestrating an online harassment campaign. Moves targeting those such as Soufan and MbN – seen in Washington as the forefront of the Middle East’s anti-Islamist extremist efforts – will harm international trust in MbS’ rule. Furthermore, there are allegations that Riyadh continues to plot against other Western-based dissidents. This is evident in the case of Omar Abdulaziz, an ally of Khashoggi’s who claims MbS has been using his family as a bargaining chip in an effort to silence him. He has also publicly warned in recent months he believes Saudi officials are plotting his murder on MbS’ orders.

At the same time, however, Biden’s rhetoric in labelling Riyadh a ‘pariah state’ should be seen primarily as positioning within the Democratic nomination battle.

One issue that has animated many on the US left, but not the voting US public more broadly, is the conflict in Yemen. The war outraged many in the Democrat party’s progressive and left wing. Biden’s warning in the same aforementioned 2019 Democratic presidential debate – that he would seek to bar arms sales to Riyadh – over the conflict is likely bluster, however. Progressives have pushed such efforts in Congress, only to be stymied repeatedly. While a Biden administration could seek limited restrictions – as Canada recently imposed – on arms sales to Riyadh, it would ultimately be unlikely to go as far as cutting Saudi Arabia off entirely, as doing so would risk leaving an opening for enhanced Russian-Saudi or Chinese-Saudi defence cooperation that Washington is keen to avoid.

Should Biden win the upcoming US election, MbS would need to quickly move to shore up ties with the new administration in order to avoid negative fallout. The tact taken by Riyadh will largely determine Biden’s policy – if MbS signals he is willing to return to relative stability, halts persecution of perceived US allies, while continuing his domestic liberalisation agenda. That MbS will pursue an agenda that seeks to restore the Saudi-US bilateral relationship to its historic position is by no means guaranteed, particularly should Biden follow through on comments indicating he would seek to revive the JCPOA – negotiated before his ascent to power. This would have both positive and negative consequences with regard to Saudi’s increasingly assertive position from a global geopolitical outlook. Firstly, it would expedite Riyadh’s inevitable agreement to normalise relations with Tel Aviv, although Gulf allies Oman and Kuwait are already following. This in turn will further erode the Palestinian – and ostensibly the ‘pan-Arab’ – goal of achieving Palestinian statehood without further erosion of territory. Lifting sanctions on Iran would however bring the country back to the negotiating table and decrease Tehran’s leverage in Iraq and Syria. Secondly, it could greatly exacerbate the crown prince’s efforts in Yemen against the Iran-aligned Ansar Allah or Huthi rebels, which would escalate the war and ruin what little faith is left to mediate the conflict. Thirdly, it would also set the stage for what appears to be a burgeoning nuclear appetite in Saudi Arabia. Should Biden not set an early limit for what actions he would tolerate from the future king in the face of increasing domestic and international aggression, the possibility to curtail MbS will quickly fade over the next four years. The prince’s ambitions and rashness have the potential to further destabilising war zones such as Libya, Syria, or east African allies and at 35 years old Muhammad bin Salman could capitalise on the Biden administration’s inertia to build a foreign policy foundation for a reign which could last for over 50 years.